Shortly before his death in 1983, pianist Eubie Blake explained the origin of the word ‘jazz’ as he recalled it. “When Broadway started to pick it up they started calling it J-A-Z-Z. It wasn’t called that. It was called J-A-S-S. That was dirty, and if you knew what it was, you wouldn’t say it in front of ladies.” Rife with sexual connotation, jass was derived as slang from the word jasm which dated to before the American Civil War and was in itself a slang euphemism for physical energy. When this new form of music began to spread beyond the brothels and gambling parlors into the mainstream culture, polite society deemed the spelling change necessary, but the meaning never changed: A delightful inside joke getting one over on that very same polite society who were now flocking to jass shows.

Prior to the advent of jazz in the years before World War I, Western music hit strictly on the beat – think of martial music or the symphonies of the day. As hard as it is to imagine, the only Western music that played around with the strict beat were the waltzes written by Johann Strauss in the latter half of the 19th Century. As jazz developed in the 1920s, musicians began to emphasis the rhythmic spaces between the notes – a little before, maybe a little after – and the concept of swinging the beat began. Many stories float around claiming that this musician or that was the first to coin the phrase and concept, but generally it seems to have come from the musical community inhabited by Louis Armstrong, Chick Webb and Earl Hines. It’s also important to recognize the influence the waltzes of the 19th Century played in helping develop swing music.

In Ten Essential Jazz Artists, Part Two we continue to look at the musicians who changed the musical paradigm of the time with their innovations. Innovations that are still in use today, regardless of genre.

Track to Hear: Black and Tan Fantasy.

EARL HINES. Nicknamed “Fatha,” Earl Hines is considered the father of modern piano playing. BornEarl Hines near Pittsburgh Pennsylvania in 1903, Hines met Louis Armstrong in Chicago when both were in their early twenties. Completely enthralled with Hines’ playing style, Armstrong replaced his own soon-to-be-ex-wife Lil Hardin Armstrong with Hines. What we are completely familiar with today as jazz, rock or country piano was born from Hines’ revolutionary and fundamental changes to how musicians approached the instrument. Using single notes in a ‘stride’ fashion with the left hand and simpler accompaniment often just consisting of octaves with the right hand, Hines’ unique stops and starts and impeccable time pushed and pulled the piano from polite parlors into smokey gin mills where the instrument always wanted to play.

Album to Hear: The Quintet: Jazz at Massey Hall

CHARLIE PARKER. What Louis Armstrong started as a virtuoso soloist in the 1920s, Charlie Parker (1920-1955) took to a cosmic level in the 1940s. Nicknamed ‘Bird’ and ‘Yardbird,’ Parker is synonymous with be-bop, the form of jazz modern listeners are most familiar with. The be-bop quintet (drums, bass, piano, saxophone, trumpet), first assembled by Parker in the late 1940s became the accepted form of the music for the next two decades. Parker’s zenith years between 1946 and 1952 were eventually cut short by his struggles with addiction and ensuing health problems. Much of the negative stigma attached to be-bop music in the years since came from Parker’s public struggles, but his music was profound and simple, elegant and brash. A decade before ‘Clapton Is God’ graffiti appeared on city walls in Europe and the US, ‘Bird Lives’ graffiti appeared in Greenwich Village after Parker’s death.

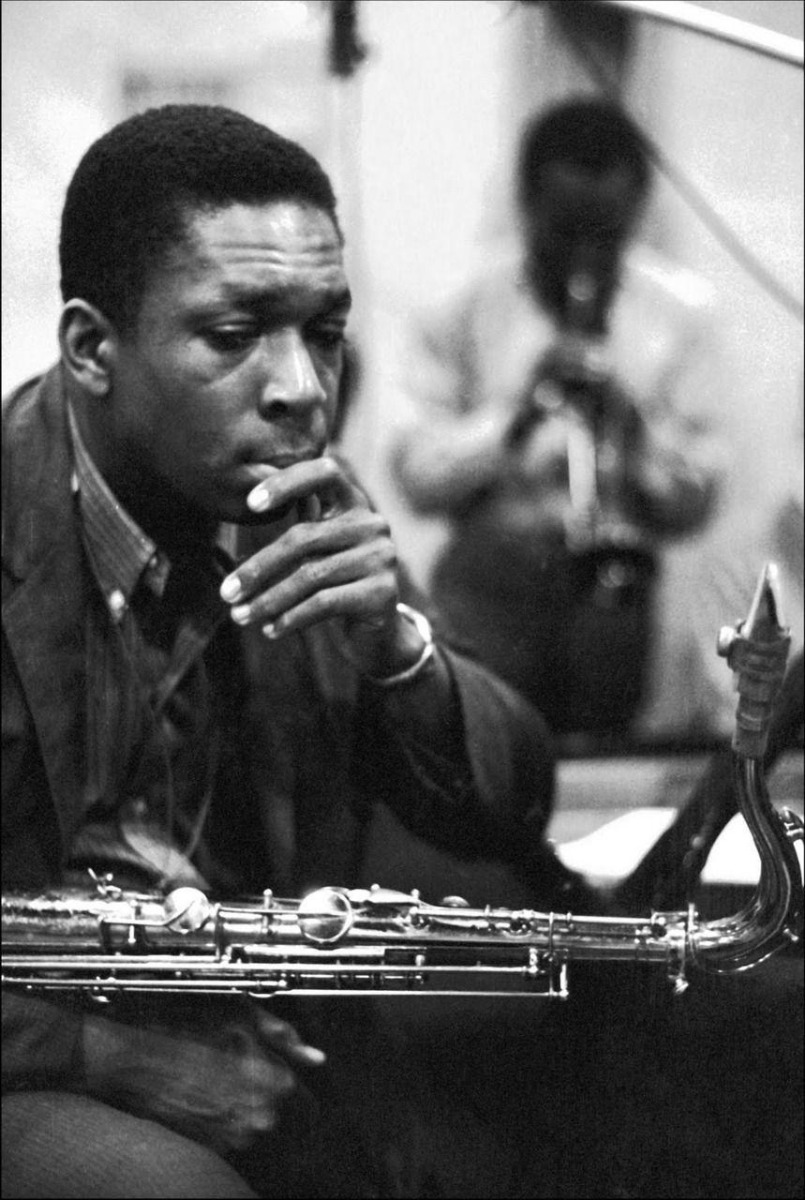

Album to Hear: Blue Trane.

JOHN COLTRANE. If Parker was the bridge between the original jazz pioneers and the be-bop era, John Coltrane (1926-1967) was the bridge between be-bop and avant-garde jazz. Born in North Carolina, Coltrane was the antithesis to Charlie Parker. Where Parker was flamboyant and idiosyncratic, Coltrane was shy and cerebral. Where Coltrane was a self-taught musician, Coltrane attended the prestigious Ornstein School of Music in Philadelphia. Coltrane developed a unique style of playing, sometimes referred to as “sheets of sound” where he cascaded notes from up to four separate chords at one time, often playing at a blistering pace of up to 1,000 notes per minute. First-time listeners often have trouble deciphering what they’re hearing, especially because the blistering pace often makes the rhythm seem disjointed, but beneath the hurry and fury lies an often overlooked simple and sweet softness. Parker died at age forty of hepatitis, which was often attributed to his earlier heroin addiction, another tragic result that unnecessarily sullied the image of the music he made.

Album to Hear: Showcase

PHILLY JOE JONES. There are dozens of drummers with more acclaim than Joseph “Philly Joe” Jones, (Chick Webb, Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, Max Roach and Art Blakeley to name just a few), but Jones’ contributions to be-bop and free jazz cannot be underestimated. Born in 1923 in Philadelphia, Jones was the consummate jazz sideman, recording with both Miles Davis and John Coltrane, among scores of others; he continued to record until shortly before his death in 1985. Listen intently to Jones’ work on albums like John Coltrane’s Blue Trane to hear a style of drumming that was so groundbreaking it is still unique even today. Rather than push the beat along from underneath, Jones’ style literally pulls the lead instruments into his rhythm leaving the bass to maintain the groove. Jones’ influence can be heard in the drumming of such disparate drummers as Ian Paice, Charlie Watts, Mickey Hart, Neal Peart, Billy Cobham and Carl Palmer.

MILES DAVIS. Like Louis Armstrong, the depth and breadth of Davis’ career far exceeds the scope of this article, so we’ll take a look at one of the most important records of the modern jazz era, Sketches of Spain. Influenced by his wife Frances’ passion for flamenco, Davis recorded a mix of traditional Spanish folk songs and along with arranger Gil Evans, produced a work that is at once other-worldly modern and timelessly traditional. Sketches of Spain is the bridge between the 1950s and pretty much every other jazz music afterward. Critically acclaimed upon its release, Sketches was not an overly popular work among Davis’ fans, but more than any of his other works it has withstood the test of time while remaining vitally modern to this day.

If you’re not overly familiar with jazz as a culture and genre, take advantage of the myriad ways we have to bring new music into our homes and go on a journey of exploration that may just change your relationship with all forms of music. The history of jazz is the combined history of technology, race, culture, artistic expression, human frailty and human triumph over astounding odds.

There is no time like the present to take a look back at how we got where we are today.